Ever since the redaction of the Mishna, halakhic texts (whether oral or written) have occupied a place of great prominence in the Oral Law. Some texts, such as the Talmud Bavli or Shulhan Arukh, have enjoyed greater standing than others. Some explain this greater standing as formal authority, with halakha described in positivist, civil law terms. I argue that such claims are not only ahistorical, they also lack a basis in law.

This is not to say these texts lack authority. Instead, these texts enjoy tremendous informal authority—some, even conventional authority at the national level. These texts are treated as authoritative by poskim because of their long history as central precedents in Jewish law, because they have become widely accepted and have been cited and commented on extensively. These qualities are what makes them canonical works of halakha.

I begin by describing the main forms of formal authority in halakha, mainly the Sanhedrin (national supreme court) and the hierarchy of courts, followed by a discussion of informal authority. Then I turn to critically examine the claim of Oral Law texts to formal authority, as illustrated by one prominent positivist model. Lastly, I offer further evidence from Hazalic texts that Hazal largely worked through decentralised and informal authority.

Types of authority and law in halakha

Jewish law is a tapestry in which God-given and man-made law are tightly interwoven. Somewhat obviously, the first source of authority in Judaism is God. The Torah, legislated by God, is the eternal statute of Am Yisrael; since it has been given, it cannot be altered (even by divine will, even through a prophet)—לא בשמים היא. This immutability covers both the actual text of the five books of written Torah and those exegeses which were received at Sinai, which is what I refer to as Sinaitic Law. Sinaitic law corresponds to law on which the Sanhedrin can technically be in error (הוראת טעות)—and, under certain conditions, may have to bring a sacrifice for leading the people astray.1

Many readers will be familiar with the de’oraita vs. derabbanan distinction. Sinaitic law is not quite the same thing as de’oraita. Sinaitic law is an essentially fixed body of law; anything beyond direct application of those laws is not Sinaitic law. De’oraita is a status which applies to a broad set of precedents derived from Sinaitic law; a posek may rule that using an electric car counts as one of the thirty-nine labours forbidden on shabbat; since this pesak din is derived from a de’oraita prohibition, it is a de’oraita-level precedent, but the rule laid down by this precedent does not form part of Sinaitic Law.2 A different way of putting it is that de’oraita and derabbanan3 are categories based on the ultimate source of the law, whereas Sinaitic law is a category based on the law’s author.

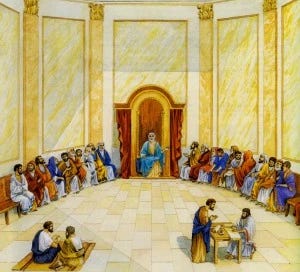

Next to Sinaitic law there is Sanhedrinal law. The Sanhedrin (Beth Din Hagadol)4 was the highest court of Am Yisrael. Its formal authority is understood to derive from the Torah, most often through the delegation of authority described in Devarim 17:8-10.5 Subject to the constraints of Sinaitic Law, precedents issued under the Sanhedrin’s authority enjoy national formal status and are binding on lower courts and the whole Jewish people.

Two notable forms of formal authority, related to the Sanhedrin, are the office of Nasi (also known as Patriarch) and the semikha (ordination). The Nasi chaired the Sanhedrin, had various important functions within it, and served as the head of the community in Eretz Yisrael for much of the Rabbinic period. The semikha, passed from down rabbi to student in a formal ceremony, qualified one to rule in certain areas of law, most notably capital cases (dinei nefashot) and cases involving fines (dinei kenasot). Thus, a samukh (ordained rabbi, sometimes called מומחה, expert) was qualified to be appointed to the Sanhedrin or a local court of deciding cases involving fines or the death penalty. The process of ordination is only allowed in Eretz Yisrael, where courts of semukhim (ordained rabbis) existed. Outside Eretz Yisrael, courts could not technically rule in matters which required semikha, but were allowed to issue formal rulings in other areas, in which they were considered to act as delegates (שליחים) of the courts in Eretz Yisrael.

The history of the Sanhedrin (as well as the semikha and Nasi) is shrouded in not a little fog; though it is attested in multiple sources, both Jewish and non-Jewish, at least some disagreement exists regarding the functioning of the Sanhedrin or its authority in virtually every time period. Firstly, regarding the Second Temple period, some argue that the Sanhedrin was controlled by the Sadducees, with proto-rabbinic movements such as the Pharisees being uncommitted to it.6 Secondly, the Sanhedrin is recorded as having moved from its seat in the Temple to a different meeting place in Jerusalem, and after the destruction of the Temple, to Yavne, from which place it would continue to travel in following generations. There are Talmudic sources which suggest that the majority’s power to force a decision was in question among Tannaim, and Rishonim are similarly divided on whether the court retained the same authority after moving, especially given the apparent centrality of the Sanhedrin’s meeting location in Devarim 17:8. Lastly, there is a disagreement as to when the Sanhedrin stopped functioning altogether. Hazalic literature makes no reference to such an event, but merely refers to Tiberias as the last (or merely most recent) place where the Sanhedrin met. Rambam states that the Bet Din Hagadol had become defunct some time before the writing of the Talmud, but offers no details.

385 and 425 CE are often cited today as the date of the abolition of the office of Nasi (also known as the Patriarchate) at the hands of the Roman authorities, which is often assumed to also have meant the demise of the Sanhedrin. However, the historical record is not clear. It certainly seems true that the office of Nasi met its end at about that time. The direct cause, however, was a lack of heir, with the role of the Romans being less clear. We have no records of the Romans abolishing the patriarchate or disbanding the Sanhedrin. The closest thing we have a record of is a law from 429 CE, appropriating the tax collected by the Nasi (from Jewish communities around the empire) to the Imperial treasury.7 There is nothing in the law’s text to indicate abolition or banning of the Patriarchate or related offices. In fact, the law implies that, other than the Nasi, Jewish communal authorities continued to function, since they were expected to continue to oversee collection of the tax in future. Specifically, the law refers to the ‘primates of the Jews, who are nominated in the Synhedriis8 of either of the provinces of Palestine’.

Thus, the extinction of the line of Nasi may have been convenient to the Roman authorities, but it is not clear they used it to disrupt the Jewish community’s functioning or to end its remaining religious autonomy. Moreover, as some scholars have argued, ‘there is no reason to assume that the Jewish community would allow Roman procedure to determine the status of its internal governing organs’9—so even if the Romans had decreed that the Sanhedrin be disbanded, it seems extremely likely that it would have continued in hiding. Such a scenario is consistent with Talmudic descriptions of the illicit continuation of semikha during times of persecution. At least one source from relatively soon after its supposed dissolution suggests that it did continue: Seder Olam Zutta records that Mar-Zuttra III travelled from Bavel to Eretz Yisrael in 520 CE to become head of the Sanhedrin. While it is impossible to know whether this court was a direct continuation of the previous Sanhedrin, the Geonic-era community of Eretz Yisrael clearly held that its institutions and semikha were indeed such a continuation.

At any rate, the authority of Sinaitic law and Sanhedrinal law is obviously national and formal in nature, whereas the authority of rulings by local courts, is not national. Whether or not a local ruling holds formal authority is a question of context. Local courts have the formal authority to make all kinds of rulings, from enforcing loans to approving a conversion, but the precedential value of those rulings can only hold formal status for the community over which the court holds jurisdiction. For other purposes, especially how a posek should rule in a different community, such local rulings set an informal precedent. What this means is something I will explore more in my next post, but for now, the important thing is that informal does not mean unimportant; indeed, over time informal precedents can become highly authoritative.

Local authorities with formal halakhic authority include local Batei Din (courts) and a Moré De’atra (community rabbi). Courts are supposed to have at least three members. However, precedents exist in the Talmud for a court of one or two to exercise (formal) judgement in some kinds of cases, at least if led by an expert in the law (יחיד מומחה) or if the parties involved in the case accepted the court upon themselves—although it is probably easier for another court to review and reverse the outcome of the case, potentially at the original judge’s expense.

Court hierarchy and the development of halakha

How do Jewish courts and rabbis create ‘new’ law? Firstly, they do so much in the same way as I described common law: through casuistic extension of rabbinic precedents to derive new precedents. Precedents can come in the form of actual case law or through instruction (hora’a) by a court, but, at other times, it takes the form of instruction by individual rabbis, responsa, codifications, commentaries and other forms of rabbinic composition, as well as precedents from practice (ma’asim). As we saw, the disappearance of semikha means courts today are limited in which cases they can rule on formally. But anyone can offer an opinion, possessing informal authority, on any part of halakha. Even before the demise of the Sanhedrin, and certainly since then, the oral law has mostly been conveyed and developed through such means, rather than formal national rulings.

Secondly, more rarely, Jewish courts legislate (create positive legislation). Unlike in modern states (either common law or civil law), in which the separation of powers holds, all Jewish courts can also issue positive laws for the communities within their jurisdiction. I term such laws (gezeirot and takannot) decrees.10 Many decrees are ascribed to Biblical figures—Joshua, King David, Ezra the Scribe. But other decrees are described in Hazalic literature with more ambiguous sense of their origin, be it national or local. It seems likely that many national rabbinic decrees are the result of similar decrees being in various places on a local basis before being confirmed or at least accepted by the Sanhedrin. In any case, we are rarely given the original text of such a decree—we usually just have precedents indicating its original content, or, more often, just the case law based on it.11 The making of decrees continued in post-Talmudic times, always with local authority: take for example Rabbenu Gershom’s decree banning polygamy or the many decrees of the Geonim.

Where there is a formal hierarchy, rulings by a court can bind lower courts. All national court rulings, or, at least, that of the Sanhedrin, are binding over local courts. One enforcement mechanism for this principle is prescribed by Torah law: a ‘rebellious elder’ (זקן ממרא), meaning an ordained rabbi who deliberately made a ruling which contravened a Sanhedrinal decision, is liable to the death penalty. Since the Sanhedrin rendered the death penalty obsolete by moving out of its prescribed seat in the Temple, this punishment is held to be inoperative, but Sanhedrins in some later periods continued enforcing the principle through niduy (excommunication). Similarly, where a regional court was established with jurisdiction over multiple local courts (think Council of the Four Lands), that court’s rulings bind the local courts subject to it.

However, no court’s power is unconstrained: Unlike modern constitutional courts, the Sanhedrin’s own instruction can be invalid, specifically if it violates basic Sinaitic Law. At least in some areas, the judgement of a local court can potentially be reversed by a different court (as Hazal very understandably discourage this course of action, there is a strong norm for judges to defer to their colleagues in a different court). Since a Beth Din’s authority is formal, only a formally-constituted court (of equal or greater authority) has the authority to review its rulings.

Though, as we’ve seen, halakha has formal rulings and decrees—formal decisions rendered by formal bodies—halakhic discussions and decision-making is largely based on precedents. Most precedents draw on an earlier source, which may hold some kind of formal authority. If they do not, their sole inherent authority12 derives from the authority of their authors. Even a ruling based on Sinaitic Law may be rendered by someone with no formal authority; the likelihood that such a ruling will be taken seriously, however, depends on the identity of its author—and the informal authority that comes with it. After a precedent is created, its authority can grow further by being cited by other precedents upholding the same judgement.

The influence of rabbis and their halakhic works among the Jewish people have stood primarily on this kind of informal authority. In this, halakha is comparable to common law systems, where the relative authority of different precedents derive partly from the earlier source, if they have one, partly on the identity of the judge or jurists who set the precedent, and partly on how it is accepted into later jurisprudence.13 Who holds this kind of informal authority? Naturally, this is harder to define than formal authority, but the key to it usually includes expertise, wisdom and persuasiveness of their arguments, However, it is also undoubtedly affected by criteria which should arguably less important, such as his personality, charisma, or appeal to the community’s ethos.

Regardless of how it is achieved to begin with, much of the stature of a posek depends on how frequently others rely on his rulings. The number of people turning to a posek is seen as a reflection of how ‘authoritative’ he is,14 and the greater the pressure there will be on others to take his view into consideration. Similarly, halakhic works gain informal authority (or even a perceived status of ‘canonicity’), in large part owing to commentaries being written on them or otherwise being cited by other halakhic works. A posek can become a major authority when his rulings or halakhic works achieve widespread acceptance, even to the extent that other poskim in their area of influence will find it (socially) difficult to rule against him, or at least that ruling against him will require an explanation. This kind of informal authority is very important in practical halakhic rulings, as the authority of prominent poskim are frequently used as a heuristic to support or at least permit a position (‘יש על מי לסמוך’).15 Neither conventional nor lesser forms of informal authority are black or white or easily measurable; they come in many degrees. Naturally, they also vary between different communities, especially when those communities have been separated by geography and language. I believe this description broadly characterises the development of authority both in modern times and in earlier periods.

An argument related to mine is made by Rabbi Joshua Berman. R. Berman makes the case that halakha functioned as common law, specifically during the First Temple Period. But what he means is distinct from my claim that halakha functions like common law (today, and most likely going back to Second Temple times, if not earlier). Instead, what he means is that the Written Torah was not treated as a statute—that its laws were treated as precedents, and not necessarily binding ones.16 Whether or not this is true, what we see from various Second Temple accounts, is that certainly by that time, the Written Torah is treated like statute law. However, its interpretation still occurs in a process which is fairly decentralised institutionally and in terms of legal interpretation is largely focused on precedent, as in common law, rather than direct application of the text itself, as in civil law. This is my argument: not that halakha was ever devoid of statute law (as Berman contends) in practice, but that halakhic practice is driven largely by precedent—precedents often derived from Torah (statute) law.

Authority of the Oral Law texts - the positivist approach

Given the prominence given in rabbinic literature to the concept, supported by explicit Torah verses, of halakha being developed by a national court with formal authority to do so, it might seem natural to assume that halakhic rulings presented by Hazal originate with such a national court. Indeed, as I mentioned in the introduction, this has been the argument or working assumption of at least one branch of rabbinic thought. One important representative of this approach in the recent period is Hakham José Faur z”l, much of whose argument is summed up in his 2010 book, The Horizontal Society.

Hakham Faur seems to view the Talmud Bavli essentially as a set of binding precedents issued by a national court (what I call a Sanhedrin). Faur describes the Talmud Bavli as a product of the discussions held at the Kalla meetings of the Babylonian academies during the Amoraic era. The Kalla was a ‘was a month-long convention during which students and sages from all over the Jewish world gathered to study to study a Talmudic Tractate… students and sages attended the classes, symposia (מתיבות) and judicial deliberations offered by the Yeshiba faculty… At these meetings, matters of law raised by local communities all over, as well as issues of national policy, were deliberated and brought to conclusion.’ (Faur 2010, 293-4). It was at these meetings, Faur contends, that most of the discussions recorded in the Talmud Bavli took place, and these records were compiled to make the Talmud Bavli, and finally redacted under the direction of Rav Ashey and Ravina (who died, respectively, in 426 and 422 CE), who headed what Faur calls the ‘National Court’ (292-3).

Though he does not say so explicitly, Faur seems to view the authority of the Talmud Bavli as somehow resulting from both the authority of the ‘National Court’ and the circumstances of the Kalla, where ‘The study, final approval and revision of the text were conducted in the general assembly, with the participation of all the sages of Israel and their disciples. Thus, the Talmud represents the views “of all or the majority of the sages of Israel.” Its authority derives from the fact that it was “approved by all Israel.”... Its authority rests on a single fact: it represents national consensus.’ Both of the quotations Faur brings are from Rambam’s introduction to Mishne Torah. Regarding the National Court (which Faur elsewhere calls the ‘Talmudic Court’ or ‘Supreme Court’), it is clear he sees it as having imbued the Talmud Bavli with formal national authority, with courts in the post-Talmudic age only holding local jurisdiction (296). He even states that, ‘With the dispersion of the Jewish communities and subsequent loss of central authority, the Mishna and Talmud, set by the last national authority of Israel, became the statutory law of the Jews” (407).

There are therefore two main arguments here, and I will comment on them separately. Firstly, that the late-Amoraic apex court in the Babylonian Jewish community was endowed with formal national authority, having binding authority over all Jewish communities (i.e. a Sanhedrin). This court is held to have redacted and signed off on the Talmud Bavli, by this endorsement making the Bavli a formally-binding halakhic text at the national level.

One problem with this argument is that the text of the Bavli continued being edited for some time after Ravina and Rav Ashey, as acknowledged to be the case both by the Rambam and other Rishonim, as well as modern academics. The continued editing suggests later generations did not see themselves as being bound by those previous precedents, or as having a lesser authority to set new precedents.

A much bigger problem, however, is how the Sanhedrin got to Bavel at all, which Hakham Faur does not address. Though, as we saw, the history is not unambiguous, we have clear records that the Nasi functioned in Eretz Yisrael right up until just after Ravina and Rav Ashey are recorded as having passed away, as well as suggestive evidence that the Sanhedrin continued functioning there after 429 CE, and again that was functioning (well enough for a leading Babylonian sage to come and join it) in 520 CE, in the middle of the Savoraic period when the Talmud Bavli was still being edited. There are, as I have alluded, claims that the Sanhedrin was disbanded sometime during this period, but it seems these claims first began to be voiced many centuries later, no earlier than the competition between the Babylonian and Eretz Yisrael centres began during the Geonic era. Apart from historical evidence, there is a halakhic problem. As the Talmud Bavli itself records, semikha can only take place in Eretz Yisrael, and ordination is required to serve on the Sanhedrin. Jewish courts in Bavel were not courts of semukhim but technically carried out judicial functions as delegates of the courts in Eretz Yisrael (שליחותייהו קעבדינן). The Rambam codifies these same rules in Mishne Torah, alongside the ruling that the last functioning Sanhedrin sat in Tiberias, as is also recorded in the Bavli. If the redactors of the Talmud Bavli thought they held formal authority equivalent to that of a Sanhedrin, they don’t seem to have told us.

Which brings us to Hakham Faur’s second argument: that the composition of the Talmud at the public sessions of the Kalla, bringing together all the sages of Babylonia, imply that its conclusions enjoyed broad rabbinic consensus representing most if not all rabbis of the time. It is not clear what kind of authority this process is supposed to have produced. It would be very difficult to argue that this authority is formal. There is no precedent or discussion anywhere in Hazalic writings that suggests the Sanhedrin’s formal authority—authority which the Torah itself commands us to heed— may transfer to a person, body or text enjoying consensus (or even unanimous) support. Majority rule, while a formal rule in halakha, applies as such in the decision-making of a single court, not in disputes between different rabbis or courts which are not subordinate to each other.17 National formal authority belongs to the Sanhedrin, constituted of ordained rabbis (semukhim), in the land of Israel. Even the Rambam’s proposal for reconstituting the Sanhedrin does not omit these factors, and it is silent on the possibility of establishing a similar body elsewhere simply by means of rabbinic consensus.

On the other hand, if the argument is that the Kalla sessions endowed the Talmud Bavli with informal authority,18 then it makes sense―and is certainly an interesting point.19 The perhaps more common focus of arguments based on consensus or universality would seem to be how widespread the influence of the Bavli would become after it was authored. During the Geonic period, after the Talmud Bavli was essentially sealed, two Jewish centres existed: one in Bavel and one in the Land of Israel, each with its distinct halakhic tradition. The latter tradition was in large part rooted in the Talmud Yerushalmi rather than the Bavli. Only after the Eretz Yisrael community was largely destroyed in the Crusades did the Talmud Bavli become truly universally dominant, although the influence of that community would continue to manifest itself in various halakhic practices (especially, but not exclusively, among Ashkenazi communities). Somewhat comparably, the Shulhan Arukh gradually gained conventional status after first being published, slowly gaining general acceptance (specifically in its dual form R. Karo’s original and the one read together with the Rema’s glosses). What cannot be said for the Shulkhan Arukh, however, is that it was produced in an open, consensus-seeking process which granted immediate informal authority. Instead, before it gained widespread acceptance, its (informal) authority stemmed solely from its author’s personal halakhic stature.

Texts of the Oral Law and how the Sages saw halakhic authority

There is much in the ancient Oral Law texts which should be fairly puzzling from a civil law perspective. Halakhic authority. The Mishna, Talmudim, and other Hazalic writings are hardly simple lists of commands and instructions, unlike the typical statute or law code. Even after separating the halakhic material from the aggadeta, they are replete with ambiguities, undefined terms, and most importantly, records of dissents (where an anonymous or ‘rabbis’ opinion is presented alongside one or more dissenting opinions) and disputes (where only named opinions are mentioned, with no ‘majority’ position). These disputes come with varying levels of indication of how they ought to be resolved, including, often, no indication.20 The Mishna offers an explanation for the inclusion of dissenting opinions, but this explanation is itself neither free from ambiguity nor from dissent (!), so that it is left unclear from the Mishna whether, or when, dissenting opinions may be followed. The issue of dissenting opinions cannot simply be dismissed by saying that they were left to be resolved by rules of pesak. Even the most well-known rule for resolving Tannatic disputes (mentioned in M. Eduyot 1:5), following the majority (יחיד ורבים הלכה כרבים), is not always followed in the Talmud or by poskim— especially where the minority opinion is found to have a superior argument.21 Imagine if US Supreme Court rulings worked like that―it would certainly give them a very different character.

Moreover, later generations do not always seem to treat the Mishna as being law in a formally authoritative sense. For example, there are a few times in the Mishna where it is stated explicitly that the halakha follows a named position (e.g. Peah 3:6, Shevi’it 9:5).22 Amoraim do not feel themselves bound by these statements, and the Talmud often concludes the halakha differently. Similarly, the anonymous statements of the Mishna―arguably, one step down in explicitness―are usually the ones accepted as halakha over any dissents, but not always. Rabbi Yohanan is best known in the Talmud as upholder of the principle of the ‘stam’ or anonymous Mishna, but most Amoraim seem to have held that there are exceptions. Another example is tum’at ba’al keri, which is recorded in Mishna Berakhot, but, we are told in the Talmud (B. Berakhot 22a), was abolished during the Amoraic period. This abolition, it seems, had its roots in with a single Tanna, Yehuda ben Beteira. Though in his time, the takanna was an established rule, Ben Beteira didn’t wait for the Sanhedrin to abolish it; he ruled it void based on his own derasha. In the Talmud, this is neither questioned nor explained.

Another episode which is difficult to explain within a perspective which sees halakha as driven by formal authority appears later in Berakhot (37a):23

Rabban Gamliel, Nasi of the Sanhedrin, and other Sages were seated together, and dates were brought before them. After everyone partook of the dates, Rabbi Akiva was given permission to recite a berakha for everyone, which he did by saying a single berakha ―contrary to Rabban Gamliel’s position that a full Birkat hamazon should be said. Rabban Gamliel got angry and said: ‘Akiva, until when will you continue to stick your head into disputes?’ Rabbi Akiva replied, saying: ‘Our teacher, even though you say this while your colleagues disagree, was it not you who taught us that in a dispute, the majority opinion is to be followed?’

If the dispute R. Akiva refers to (presenting it no differently than the Talmud might present a dispute) was resolved by vote of the the Sanhedrin, what reason could Rabban Gamliel possibly have for criticising him? Moreover, if the dispute had been resolved in such fashion, why does R. Akiva present it as a live dispute rather than a decided matter? On the other hand, if the Sanhedrin had not yet voted, but was going to, R. Akiva’s argument, that the majority should be followed, could only be referring to an informal principle which informs halakhic decision-making, not to the formal decision rule in a Sanhedrinal vote―which had not yet been held. It still raises the question as to why he thought this principle to be more important than deferring to his teacher or to the Nasi - both of which were legitimate options as long as the Sanhedrin had no make a final ruling. Though this is not conclusive, I think this story is easiest to reconcile with a reality in which the Sanhedrin had not decided, nor did the individuals in the story seriously expect the Sanhedrin to resolve the question; instead, halakhic decision-making was decentralised in practice, and the exchange illustrates contrasting approaches to making individual halakhic rulings.

In law and politics, authority tends not to go unannounced.24 But almost nothing in these sources themselves indicates that the texts (as a whole) represent national Sanhedrinal rulings (nor that they were canonised and elevated to a comparable level by some late centralised decision). Much (not all) of Hazalic literature may have developed in the Sanhedrinal yeshiva, but that would not make all teachings contained in them Sanhedrinal rulings. Some teachings (especially from Yavne) are recorded by Hazal as having been voted on or received from the Sanhedrin, but such attestations are not very common; if anything, they suggest that Sanhedrinal precedents are but a small part of the teachings recorded in them. Indeed, it seems that the Sanhedrin mostly did not play a major role in resolving disputes (see Safrai 2022). In Yavne, the one generation which saw a systematic attempt to do so, the disputes involved threatened the fragile balance of the rabbinic community with schism. For various reasons, the rabbinic leadership was usually politically and practically not in state to enforce very many decisions in a centralised manner. On the other hand, on questions where there was a broad consensus, there was probably usually little need to make official centralised rulings either. Thus, much of Hazalic rabbinic law was most likely developed in a decentralised and partly informal manner.25

All these points militate against the notion that the Mishna or the Talmudim are, or were meant as, codes of law in the civil law sense. Instead, Hazalic compositions are compilations of rabbinic teachings from different individuals and centres of Torah learning, including precedents laid down both centrally and locally. Though the editors were not neutral and often point or even declare a halakhic conclusion, the overall aim of these compositions was not to legislate (they did not have authority to do so) but to preserve the oral Torah as Hazal knew it—disputes and all. They do preserve, within them, many national decrees and binding precedents, but this is a relatively small part of what they do. The authority of these compilations, especially the Talmud, only developed in a gradual process into a well-established and widely-accepted conventional authority. This process was largely informal, meaning that it was not established by some body with (national) formal authority but became established by convention. It was therefore determined not by formal halakhic process but largely through historical and social developments.

None of this is to say that Hazalic or other texts held to be canonical lack authority—again, I argue that these texts enjoy tremendous conventional authority. Clearly, they command a huge amount of respect among poskim because of their historical development into precedents which are cited extensively and widely accepted and commented on, which is what makes them canonical works of halakha. At the same time, Hazalic literature is uniquely authoritative—as the earliest set of precedents we have on the Oral Law, and from which the vast majority of later precedents derive. A consensus of later generations deferred to them and established them as Judaism’s set of primary precedents—ones which have been widely and continuously used to determine and develop halakha.

Given all this, I would argue for a more modest account of the halakhic authority found in rabbinic texts, one with a smaller direct role for national formal authority. As I hope to have demonstrated in this post, based on its own rules regarding for formal authority, halakha’s own chief sources of law are more informal in nature, and are treated as such by the Rabbis, than civil law or positivist models of halakha would have us believe.

As we saw in previous posts, civil law is focused on formal sources of law, especially positive law, while common law need not be. In my next post, I shall aim to illustrate in greater detail what this looks like, and how the halakhic process resembles the common law tradition.

Exactly which types of derivations from Sinaitic law are de’oraita is a matter of extensive dispute among Rishonim, so I will not go into that. At any rate it is not exactly material to my argument.

Derabbanan also does not necessarily correspond to Sanhedrinal law, as we shall see.

In accordance with common usage, I will generally use the term ‘Sanhedrin’, although technically that is a name for two kinds of court: the Beth Din Hagadol (a.k.a. Court of Seventy One or ‘Great’ Sanhedrin), and a court of Twenty-Three.

The nature of this delegation is a matter of significant debate among Rishonim. E.g.רמב”ן ספר המצות שורש א, דרשות הר”ן ז.

Ze’ev Safrai in his Introduction to the Mishnah (2022, 33), claims that “there was no Pharisee Sanhedrin during the Second temple period”, and argues that the Pharisees consequently did not accept the authority of the Sanhedrin during that period. He further hypothesises that the law of Horayot, which includes an obligation for some not to follow the instruction of the Sanhedrin if they know it to be mistaken, was developed during this time. It seems clear to me, however, that there were periods of the Hasmonean Kingdom (if not also afterwards) when the Pharisees were in favour with the monarch and almost certainly did control the Sanhedrin. Moreover, holding that certain formal rulings are mistaken does not mean or require complete disavowal of a court’s authority within the system, see for example modern-day arguments over the rulings of the US Supreme Court. Lastly, Horayot does not undermine the halakhic system of authority if it can be understood as applying specifically to (parts of) the immutable Sinaitic core of halakha.

See A. Linder 1987. The Jews in Roman Imperial legislation. 320.

Linder explains that there were two ‘sanhedrins’, one in Palaestina Prima and another in Palaestina Secunda. The sanhedrin of the latter province, which included the Galilee, is likely the ‘Great’ Sanhedrin (in Tiberias) referred to in rabbinic sources.

Blidstein 1998, ‘Maimonides on the Renewal of Semikha - some historical perspective’ p27 n.5

Some prefer calling Sinaitic law the ‘constitution’ and Rabbinic takkanot or gezeirot ‘statutes’; if constitution merely means a higher level of legislation, there is little practical difference, but I think using the term ‘constitution’ tends to make people think of halakha in terms of an (erroneous) positivist framework where the rabbis are legislators and rabbinic law is legislation. As I argue here, it is not; most of halakha consists of precedents, some of which are formal binding precedents (national or local), but even these are not positive law; only the written Torah and takannot and gezeirot are positive law, and we follow them based on precedent, not their text.

Good examples include the decree on hannukah candles (B. Shabbat 21b) and the decrees ascribed to Joshua regarding land use in Eretz Yisrael (B. Bava Kama 82a)

As opposed to the authority a precedent gains after being issued through acceptance.

As we saw with Jaffey - the rule set down by common law ruling is provisional until confirmed by subsequent rulings.

Acceptance may be particularly important for single poskim, as halakha generally holds that a single-judge court only has authority over cases voluntarily referred to him by litigant and defendant.

E.g. ‘שו"ת הרא"ש כלל ב סימן ח: ‘הנח להם, כי נתלים באילן הגדול, הרב אלפסי, שמתירו

Effectively, according to Berman, all law was ‘common law’ in the case law sense of the term, whereas I argue halakha is like a common law system including both statutes and precedents.

Eliezer Berkowitz, ההלכה: כוחה ותפקידה 2007 p33; Hazon Ish (כלאים סימן א, מכתב); As we will see in the next post, majority rule is one of the main informal heuristics (or rules of thumb) in pesak halakha.

Admittedly, this does not seem to be his intention. Consider, for instance, his comments on the Ramban’s approach on vol. II page 156 (appendix 66).

Leaving aside the question of the historicity of Faur’s account of the Kalla, on which I do not know enough to comment.

Indeed, the argument that the Talmud (either one) is generally made up of Sanhedrinal rulings suggests that Hazal were (ח”ו) somewhat negligent in their transmission of the Oral Law to us, as they left it so unclear what the laws are from which a Jew (by Torah law) must not deviate “to the right or to the left”.

Eliezer Berkowitz, ההלכה: כוחה ותפקידה 2007 pp.19-39.

As an aside, if rules existed resolving all disputes in the Mishna from the time the Mishna was published (as would seem to be implied by the idea that the Mishna was created as a statutory code), this would seem superfluous.

For example, in the Geonic Era confrontations between the Academies of Bavel and the Land of Israel, both sides insistently claimed to be the legitimate central authority of the Jewish world.

Does that mean that contemporary Rabbis could theoretically introduce new “derabbanans” (rabbinic obligations) or even new interpretations of written Torah? Possibly. Significantly, however, modern poskim virtually never claim to do so (even when dealing with new phenomena such as the use of electricity), and instead almost universally extend the application of existing precedents to new cases.

Question for you: How was this development process different for *Karaite* halakha, other than for the fact that the Karaites never accepted the Mishnah to begin with due to their belief that the Mishnah was created by man and thus, while being worthy of respect, was not binding on themselves?